Sikh Anzacs

Did you know?

At least 19 Sikhs enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) in WWI.

Approx 1.2 million Indians volunteered to fight for the British Indian Army in WWI, making them the largest volunteer army in the Great War. While Sikhs only make up 2% of India’s population, 22% of the British Indian Army were Sikhs.

In World War I and II, 83,005 Sikhs were killed and 109,045 wounded fighting for the allied forces.

Sikhs continue to serve proudly in the Australian Defence Force today.

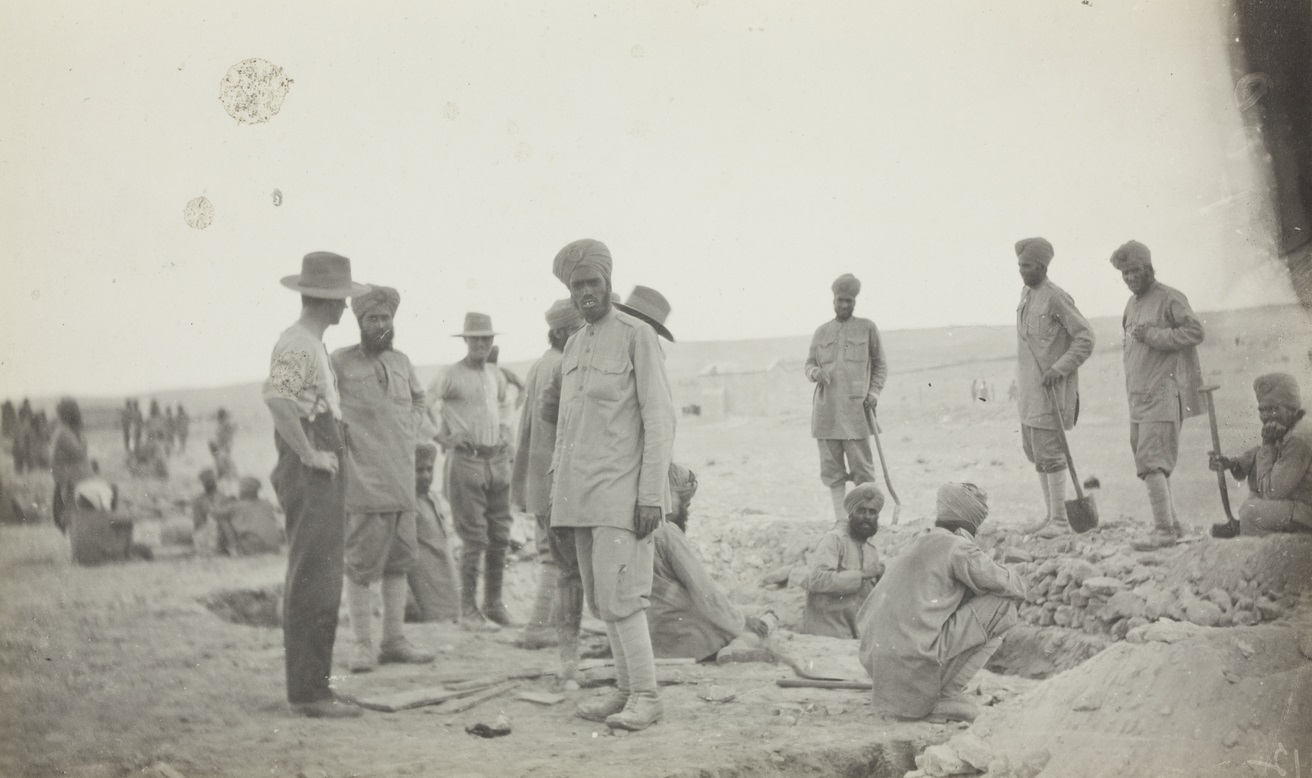

The Indian expeditionary force that served in the Dardanelles was not very large in numbers; 5,000 men in a campaign that swelled from 75,000, to nearly half a million allied troops by the end. Yet it had a significant impact upon the course of the operations, and no account of the campaign can ignore the contribution of the 14th Sikhs in the Third Battle of Krithia.

However, despite the fact that they served with honour at Gallipoli, not just with, but as a part of, the Anzacs from August onwards, this contribution has been relegated largely to a passing mention in most accounts of the campaign. It was sorely tried but emerged from the fray with credit having suffered a total of 4,130 casualties during the campaign.

The 14th Sikhs

In the Gallipoli campaign, the 14th Sikh regiment was virtually wiped out, losing 379 officers and men in one day’s fighting on 4 June 1915. Writing of the Third Battle of Krithia during the campaign, General Sir Ian Hamilton paid noble tribute to the heroism of all ranks of the 14th Sikhs:

“In the highest sense of the word extreme gallantry has been shown by this fine Battalion… In spite of the tremendous losses there was not a sign of wavering all day. Not an inch of ground was given up and not a single straggler came back… The ends of the enemy trenches leading into the ravine were found to be blocked with the bodies of Sikhs and of the enemy who died fighting at close quarters, and the glacis slope is thickly dotted with the bodies of these fine soldiers all lying on their faces as they fell in their steady advance on the enemy. The history of the Sikhs affords many instances of their value as soldiers, but it may be safely asserted that nothing finer than the grim valour and steady discipline displayed by them on 4th June has ever been done by the soldiers of the Khalsa. Their devotion to duty and their splendid loyalty to their orders and to their leaders make a record their nation should look back upon with pride for many generations.” (Gallipoli Diary, 1926)

During this battle, the 14th Sikhs (as part of the 29th Indian Infantry Brigade), composed entirely of seasoned Sikh soldiers from the Punjab, launched repeated attacks, in the face of murderous machine gun fire, against the Turkish positions astride Gully Ravine. Held up by the barbed wire that was unaffected by the allied artillery bombardment a section of men leapt the barbed wire and charged the Turks with their bayonets. However, human valour was unavailing against modern weapons of war, and on that day the battalion’s casualties amounted to 82 percent of the men actually engaged in the battle. Only 3 British officers were left unwounded.

The Forgotten Sikh Anzacs

Our research has found that the following men with the last name "Singh" and which we believe to be Sikh enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force for World War I:

Reginald Arthur Savory was born in London in 1894. He was commissioned as an officer in the 14th Sikhs in 1914. He served with them in Gallipoli in 1915. The following account of the Battle of Krithia:

“On 3rd June we received orders for general assault all along the line next day. The orders were short and clear. At 11 am on 4th June all the guns were to bombard the enemy’s front line trenches for twenty minutes. Then for ten minutes they were to stop while the infantry were to cheer and wave their bayonets. The object of this was to persuade the enemy to man their parapets. Then the bombardment was to come down again. At noon we were to advance. It all sounded simple enough. The 14th Sikhs were to attack astride the Gully Ravine.

The 4th of June was a beautiful summer day. Our guns started registering at 8 am and even before the bombardment began it must have been clear to the enemy that something was about to happen.

It was now 11.30 am and time for the cheering to start; but the noise was so great that we could hardly hear it even in our own trench. And then- twelve noon – blew the whistle – and we were away. From that moment I lost all control of the fighting. The roar of musketry drowned every other sound, except that of the guns. To try to give an order was useless. The nearest man was only a yard or two away but I couldn’t see him. Soon I found myself running on alone, except for my little bugler, a young, handsome boy, just out of his teens, who came paddling along behind me to act as a runner and carry messages. Poor little chap.

During the first few minutes, I was knocked out, lying on the parapet with two Turks using my body as a rest over which to shoot at our second line coming forward. When I fully recovered consciousness, the Turks had gone. I looked around and saw my little bugler lying dead, brutally mutilated. I could see no one else, stumbled back as best I could, my head was bleeding and I was dazed and then, Udai Singh, a great burly Sikh with a fair beard who was one of our battalion wrestlers, came out of the reserve trenches, picked me up, slung me over his shoulder, and brought me to safety; and all the time we were being shot at.”